Until the second half of the 19th century, it was believed that voting ballots - ostracа, were specially made clay tablets. Thanks to archaeological finds, it became clear that these were ordinary shards. There was no ostracon standard in terms of size, appearance and material: it could be either rough pieces of tiles or fragments of red-figure vases, as small fragments on which the inscription barely fit, or whole small vessels.

To date, archaeologists have found more than 10000 ostraca. In total, about two hundred Athenians are represented on them. The five "leaders" in terms of the number of surviving ostraca with their names include Megacles, the son of Hippocrates (4647), Themistocles (2238), Callias, the son of Cratius (720), Menon, the son of Meneclides (608), and Cimon (474). Ostraca are also sources of information on the basis of which historians draw certain conclusions. So, having studied the inscriptions on more than 700 ostraca filed against Kallius, the son of Cratius, historians have created a reconstruction of the life of an influential politician of Ancient Athens, about whom literary sources do not report anything.

Sometimes on the ostraca, people wrote the reasons why they wanted to expel someone. In this way, ostraca have become an important source of historical data.

Here are some records that have survived to this day:

It can be both short subscripts ("ίτω", "Let him go", or "έχε", "Get this"), as well as whole epigrams: "The most transgressed of the defiled pritans / This shard says - the son of Ariphron Xantippus." There was no single standard for the ostracon. In most cases, the inscriptions are invective. So, on one of the ostracons with the name Aristide, "brother of Datis" is attributed, with a hint of his pro-Persian orientation nearby.

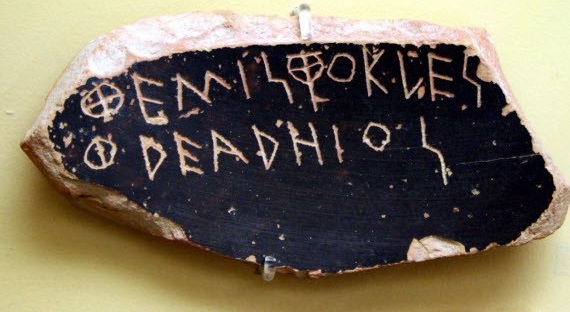

Ostraca often contain direct insults, at times using obscene language. "Themistocles, son of Neocles, asshole...(χαταπύγον)" , the word "χαταπύγον" refers to engagement as passive partner in anal intercourse. Another voter accused Themistocles of being a "pollution in the land."

For example, ostraca against Callixenus and against Leagrus explicitly label their candidates as traitors (προδοται).

On one ostracon against Callias there is even a drawing of a person (presumably Callias himself ) in Persian dress.

On five ostraca, Megacles is described as keeping horses (ιπποτροφος), a typical pursuit of the elite, and a sign of great wealth. One ostracon against Megacles even has a skillfully rendered drawing of a horse and rider.

Six ostraca explicitly associate him with a woman named Coisyra. Despite some confusion over which of several known Coisyras is meant, it seems that in fifth-century comedy the name Coisyra was associated with arrogance, ostentatious display, and ambition. One ostracon accuses Megacles of being overly fond of money a reference perhaps alluding to susceptibility to bribery in public office. Another ostracon labels Megacles an adulterer (μοιχος).

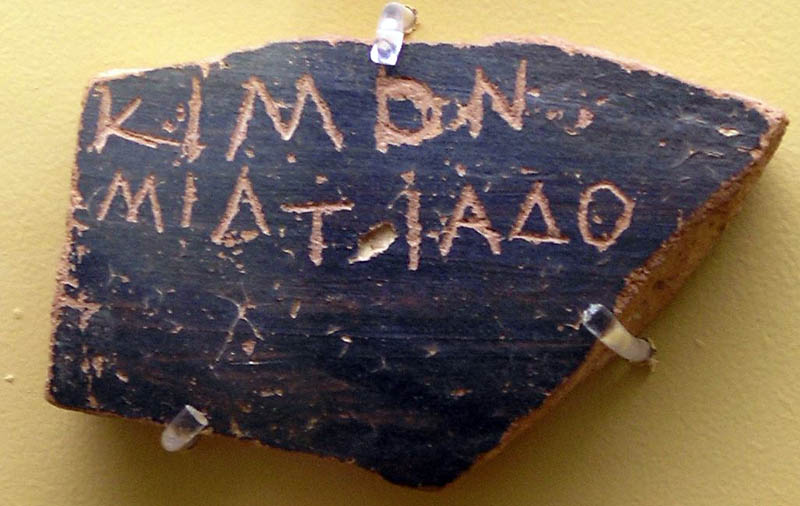

Similar accusations of improper sexual relations occur in the literary sources dealing with Alcibiades’ candidacy for ostracism, and in one ostracon against Cimon, on which a voter wrote, "Let Cimon son of Miltiades go away, taking Elpinice with him!". Since literary sources (Plutarch f.e.) report that Elpinice was Cimon’s sister and that he had an incestuous relation with her, it appears that Cimon’s violation of communal sexual norms was the reason for this vote against him.

The plethora of comments and even drawings on ostraca has only added to the variety of potential motives for ostracism. Several candidates appear to be accused of corruption in public office. Most eloquent is a potsherd against Xanthippus son of Ariphron, who was ostracized in 484 BC. On this potsherd, a voter wrote an elegiac couplet accusing Xanthippus of some sort of public misconduct: that potsherd declares that Xanthippus son of Ariphron does the most wrong of the accursed leaders. The use of the adjective "accursed" (αλειτερος) on this ostracon and on several ostraca against Alcmeonids has raised questions about the use of ostracism against those guilty of religious offenses that might pollute the entire community. Related to this interpretation of ostracism is the idea that the procedure may be associated with scapegoating and other types of rituals for expelling pollution. In these rituals, one or more persons were expelled from the community in order to purify it and prevent the gods from harming the rest of its members.

Failure to expel pollution from the community was thought to cause pestilence (λοιμος) and famine (λιμος). At Athens, two men of low social standing were annually expelled at the Thargelia festival, in early summer. Besides the obvious parallel of an annual expulsion in both scapegoating rituals and ostracism, it is striking that a number of ostraca apparently allude to the expulsion of famine via the scape-goating ritual. Seven ostraca from the Ceramicus call for the expulsion of Famine (λοιμος). One voter even added a patronymic to the personified famine, calling his candidate "Famine son of Noble Father".

Many of the surviving ostraka name people otherwise unattested. They may well be just someone the submitter disliked, and voted for in moment of private spite.

In addition to these parallels between expulsion rituals and ostracism, there are similarities between the use of inscribed potsherds in an ostracism and the practice of inscribing curses on various materials (usually lead) in order to harm a personal enemy - civic variant of Athenian curse tablets, studied in scholarly literature under the Latin name defixiones, where small dolls were wrapped in lead sheets written with curses and then buried, sometimes stuck through nails for good measure.

It is widely believed that the first three victims of ostracism were expelled due to their association with the Peisistratos. However, some researchers (in particular, B. M. Lavelle (Loyola University of Chicago)) consider this to be a delusion. In support of the version that kinship with the tyrant Pissistratus at least did not play a key role in the expulsion of the first three ostracized Athenians, shows also the fact, that for the first time the institution of ostracism was applied only 20 years after the reforms of Cleisthenes.

After Marathon, probably in 489 BC, Miltiades, the hero of the battle, was seriously wounded in an abortive attempt to capture Paros. Taking advantage of his incapacitation, the powerful Alcmaeonid family arranged for him to be prosecuted. The Athenian aristocracy and indeed Greek aristocrats in general, were loath to see one person pre-eminent, and such maneuvers were commonplace. Miltiades was given a massive fine for the crime of 'deceiving the Athenian people', but died weeks later as a result of his wound. In the wake of this prosecution, the Athenian people chose to use the new institution of the democracy - ostracism, which had been part of Cleisthenes's reforms, but remained so far unused. This may have been triggered by Miltiades's prosecution, and used by the Athenians to try to stop such power-games among the noble families. Certainly, in the years (487 BC) following, the heads of the prominent families, including the Alcmaeonids, were exiled. The career of a politician in Athens thus became fraught with more difficulty, since displeasing the population was likely to result in exile.

Hipparchos son of Charmos - 488/7 BCE

Hipparchos became the first Athenian to be ostracized. His name is attested from twelve ostraca (eleven found in the excavations of the Agora and one in the Kerameikos, Athens). According to the Atthidographer Androtion and the Aristotelian Constitution of the Athenians, Hipparchos was a relative of the tyrant Peisistratos. Hipparchos was leader (hegemon) of the "friends of the tyrants" in Athens. Almost certainly that became the main reason to expel him from Athens.

By Dionysius of Halicarnassus Hipparchos can be identified with the homonymous archon. As stated by the author of the Constitution of the Athenians, he was of the deme (political division in ancient Greece) of Kollytos, while Plutarch writes that he was of the deme of Cholargos.

Megacles, son of Hippocrates - 486 BCE

The second exile under the law of Ostracism was Megacles, son of Hippocrates (not the famous Father of Medicine), grandson of Megacles the son of Alcmaeon, nephew of Cleisthenes.

Aristotle reports the ostracism of Megakles son of Hippokrates, and goes on to say that "the Athenians continued for three years to ostracize the friends of the tyrants, on account of whom the law had been enacted" (Athenian Constitution 22). More than 4,000 ostraca bearing Megakles' name were found in one deposit in the Kerameikos (the potters' quarter of Athens) and have been associated with the ostracism of 486 B.C., although the rude comments that accompany his name on some of these ostraca concentrate on his morals rather than on his tyrannical tendencies.

Kallixenos (Callixenus) son of Aristonymos - 485 BCE

Kallixenos (Callixenus) son of Aristonymos, of deme Xypete was another nephew of Cliesthenes. There is not too much data about this person (probably he was the head of the Alcmaeonids), even not known for certain if he was the third ostracized athenian. However over 250 ostracones found from a single deposit at the Agora, point to him as "the third" and show that this man was active in the political activity of Athens. Some ostraca against Kallixenos explicitly label their candidate as traitor.

*****

Тhe next four exiles were great Athenians who played a big role in increasing the power and influence of Athens.

Xanthippus son of Ariphron - 484 BCE

Xanthippus was a wealthy Athenian politician and general during the early part of the 5th century BC. His name means "Yellow Horse." He was the son of Ariphron and father of Pericles. He is often associated with the Alcmaeonid clan. Although not born to the Alcmaeonidae, he married into the family when he wed Cleisthenes' niece Agariste. He distinguished himself in the Athenian political arena, championing the aristocratic party.

As a citizen-soldier of Athens and a member of the aristocracy, Xanthippus most likely fought during the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. Xanthippus first appears in the historical record the following year (489 BC), when he led the prosecution of Miltiades the Younger, the general who led Athenians to victory at Marathon. Athenians would come to regret their treatment of their war hero, but immediately following the trial Xanthippus became the pre-eminent politician of the day, if only briefly.

Xanthippus' leadership was short lived due to the rise of Themistocles, who was a populist set against the aristocracy that Xanthippus represented. Xanthippus teamed up with his fellow aristocrat Aristides to counter the ambitions of Themistocles, but Themistocles out-maneuvered them with a series of ostracisms that were basic referendums concerning the direction of the Athenian government. The lower classes had begun to flex their political muscle with Themistocles, and the results of the ostracisms reflected their new-found power. There were 5 prominent ostracisms of aristocrats during the political clashes of the 480's BC, and both Xanthippus and Aristides were among the victims. Xanthippus was ostracised in 484 BC.

Normally, an ostracism led to a 10-year exile. But when the Persians returned to attack Greece in 480 BC, Themistocles and Athens recalled both Xanthippus and Aristides to aid in the defence of the city. The rival politicians settled their differences and prepared for war. The city of Athens had to be abandoned to protect its citizens and Plutarch relates a folk tale about Xanthippus' dog, who had been left behind by his master when the Athenians embarked for the safety of the Island of Salamis. The dog was so loyal that it jumped into the sea and swam after Xanthippus' boat, managing to swim across to the isle, before dying of exhaustion. In Plutarch's day there was still a place on Salamis called "the dog's grave."

So, Xanthippus' rivalry with Themistocles led to his ostracism, only to be recalled from exile when the Persians invaded Greece. He distinguished himself during the Greco-Persian Wars making a significant contribution to the victory of the Greeks and the subsequent ascendancy of the Athenian Empire.

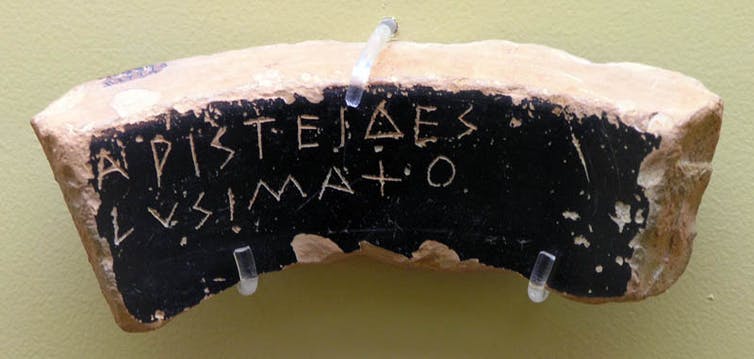

Aristides son of Lysimachus - 483 BC

Aristides was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just", he flourished in the early quarter of Athens' Classical period and is remembered for his generalship in the Persian War. Herodotus cited him as "the best and most honourable man in Athens", and he received similarly reverent treatment in Plato's Socratic dialogues.

Aristides was the son of Lysimachus, and a member of a family of moderate fortune. Of his early life, it is only told that he became a follower of the statesman Cleisthenes and sided with the aristocratic party in Athenian politics. He first came to notice as strategos in command of his native tribe Antiochis at the Battle of Marathon, and it was no doubt in consequence of the distinction which he then achieved that he was elected archon eponymos for the ensuing year (489–488 BC). Pursuing a conservative policy to maintain Athens as a land power, he was one of the chief opponents of the naval policy proposed by Themistocles.

A key basic reason in Aristides' ostracism was his rivaly with Themistocles. Themistocles with his power-base firmly established among the poor, moved naturally to fill the vacuum left by Miltiades's death, and in that decade became the most influential politician in Athens. However, the support of the nobility began to coalesce around the man who would become Themistocles's great rival—Aristides. Aristides cast himself as Themistocles's opposite—virtuous, honest and incorruptible—and his followers called him "the just". Plutarch suggests that the rivalry between the two had begun in their youth, when they competed over the love of a boy.

During the decade, Themistocles continued to advocate the expansion of Athenian naval power.The Athenians were certainly aware throughout this period that the Persian interest in Greece had not ended; Darius's son and successor, Xerxes I, had continued the preparations for the invasion of Greece. Themistocles seems to have realised that for the Greeks to survive the coming onslaught required a Greek navy that could hope to face up to the Persian navy, and he therefore attempted to persuade the Athenians to build such a fleet. Aristides, as champion of the zeugites (the upper, 'hoplite-class') vigorously opposed such a policy.

In 483 BC, a massive new seam of silver was found in the Athenian mines at Laurium. Themistocles proposed that the silver should be used to build a new fleet of 200 triremes, while Aristides suggested it should instead be distributed among the Athenian citizens. Themistocles avoided mentioning Persia, deeming that it was too distant a threat for the Athenians to act on, and instead focused their attention on Aegina. At the time, Athens was embroiled in a long-running war with the Aeginetans, and building a fleet would allow the Athenians to finally defeat them at sea. As a result, Themistocles's motion was carried easily, although only 100 warships of the trireme type were to be built. Aristides refused to countenance this; conversely Themistocles was not pleased that only 100 ships would be built. Tension between the two camps built over the winter, so that the ostracism of 482 BC became a direct contest between Themistocles and Aristides, Aristides was ostracised, and Themistocles's policies were endorsed. Indeed, becoming aware of the Persian preparations for the coming invasion, the Athenians voted for the construction of more ships than Themistocles had initially asked for. In the run up to the Persian invasion, Themistocles had thus become the foremost politician in Athens.

Early in 480, Aristides profited by the decree recalling exiles to help in the defence of Athens against Persian invaders, and was elected strategos for the year 480–479. In the Battle of Salamis, he gave loyal support to Themistocles, and crowned the victory by landing Athenian infantry on the island of Psyttaleia and annihilating the Persian garrison stationed there.

A well-known anecdote about Aristides.

On the ostracophoria day, when the Athenians were voting in their Agora, an illiterate peasant approached Aristides and handed him a potsherd, asking him to scratch on it the name of the man’s choice for ostracism. “Certainly,” said Aristides. “Which name shall I write?” “Aristides,” replied the man. Aristides, without revealing his identity, remarked “Very well. But tell me, my friend… What harm has Aristides done to you?” “Oh, nothing,” sputtered the peasant, “I don’t even know the man! I’m just sick and tired of hearing everybody refer to him as ‘The Just.’” Aristides without hesitating he proceeded to inscribe his own name on the ostrakon, and, without uttering a word, gave it back to that man…

On the example of the expulsion of Xanthippus and Aristides, we see for the first time such a clear use of the institution of ostracism in the political struggle between the ruling elites.

We also see the first application of the practice of recalling the expelled as a result of ostracism (480 BC).

Themistocles son of Neocles - 471 BC

Themistocles was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As a politician, Themistocles was a populist, having the support of lower-class Athenians, and generally being at odds with the Athenian nobility.

Themistocles was born in the Attic deme of Phrearrhioi around 524 BC, the son of Neocles, who was, in the words of Plutarch "no very conspicuous man". His mother is more obscure; according to Plutarch, she was either a Thracian woman called Abrotonon, or Euterpe, a Carian from Halicarnassus. Like many contemporaries, little is known of his early years. Some authors report that he was unruly as a child and was consequently disowned by his father. Plutarch considers this to be false. Plutarch indicates that, on account of his mother's background, Themistocles was considered something of an outsider; furthermore the family appear to have lived in an immigrant district of Athens, Cynosarges, outside the city walls. However, in an early example of his cunning, Themistocles persuaded "well-born" children to exercise with him in Cynosarges, thus breaking down the distinction between "alien and legitimate". Plutarch further reports that Themistocles was preoccupied, even as a child, with preparing for public life. His teacher is said to have told him: "My boy, you will be nothing insignificant, but definitely something great, either for good or evil."

On the back of his popularity, he evidently decided to run for this office and was elected Archon Eponymous, the highest government office in the following year (493 BC). Themistocles's archonship saw the beginnings of a major theme in his career; the advancement of Athenian sea-power. Under his guidance, the Athenians began the building of a new port at Piraeus, to replace the existing facilities at Phalerum. Since Athens was to become an essentially maritime power during the 5th century BC, Themistocles's policies were to have huge significance for the future of Athens, and indeed Greece. In advancing naval power, Themistocles was probably advocating a course of action he thought essential for the long-term prospects of Athens. However, as Plutarch implies, since naval power relied on the mass mobilization of the common citizens (thetes) as rowers, such a policy put more power into the hands of average Athenians—and thus into Themistocles's own hands.

During the first Persian invasion of Greece he fought at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC) and was possibly one of the ten Athenian strategoi (generals) in that battle.

In the years after Marathon, and in the run-up to the second Persian invasion of 480–479 BC, Themistocles became the most prominent politician in Athens. He continued to advocate for a strong Athenian Navy, and in 483 BC he persuaded the Athenians to build a fleet of 200 triremes; these proved crucial in the forthcoming conflict with Persia. During the second invasion, he effectively commanded the Greek allied navy at the battles of Artemisium and Salamis in 480 BC. Due to his subterfuge, the Allies successfully lured the Persian fleet into the Straits of Salamis, and the decisive Greek victory there was the turning point of the war. The invasion was conclusively repulsed the following year after the Persian defeat at the land Battle of Plataea.

Due to the threat of a Persian invasion, he was forced to withdraw from exile his political opponents Aristides and Xanthippus and ask to unite in the fight against the enemy. It is probable that in early 479 BC, Themistocles was stripped of his command; instead, Xanthippus was to command the Athenian fleet, and Aristides the land forces. Though Themistocles was no doubt politically and militarily active for the rest of the campaign, no mention of his activities in 479 BC is made in the ancient sources. In the summer of that year, after receiving an Athenian ultimatum, the Peloponnesians finally agreed to assemble an army and march to confront Mardonius, who had reoccupied Athens in June. At the decisive Battle of Plataea, the Allies destroyed the Persian army, while apparently on the same day, the Allied navy destroyed the remnants of the Persian fleet at the Battle of Mycale. These twin victories completed the Allied triumph, and ended the Persian threat to Greece.

After the conflict ended, Themistocles continued his pre-eminence among Athenian politicians. However, it seems clear that, towards the end of the decade, Themistocles had begun to accrue enemies, and had become arrogant; moreover his fellow citizens had become jealous of his prestige and power. The Rhodian poet Timocreon was among his most eloquent enemies, composing slanderous drinking songs (btw this is one of the oldest references to negative campaigning). He also lost favor by building a sanctuary of Artemis, with the epithet Aristoboulẽ ("of good counsel") near his home, a blatant reference to his own role in delivering Greece from the Persian invasion. Eventually, in either 472 or 471 BC, he was ostracized.

In itself, this did not mean that Themistocles had done anything wrong; ostracism, in the words of Plutarch, "was not a penalty, but a way of pacifying and alleviating that jealousy which delights to humble the eminent, breathing out its malice into this disfranchisement."

After Themistocles was ostracized, he went into exile in Argos. The Spartans now saw an opportunity to destroy Themistocles, and implicated him in the alleged treasonous plot of 478 BC of their own general Pausanias. Themistocles thus fled from Greece. Alexander I of Macedon (r. 498–454 BC) temporarily gave him sanctuary at Pydna before he traveled to Asia Minor, where he entered the service of the Persian king Artaxerxes I (reigned 465–424 BC). He was made governor of Magnesia, and lived there for the rest of his life.

Cimon son of Miltiades - 461 BC

Cimon was an Athenian statesman and general in mid-5th century BC Greece. He was the son of Miltiades, the victor of the Battle of Marathon. Cimon played a key role in creating the powerful Athenian maritime empire following the failure of the Persian invasion of Greece by Xerxes I in 480–479 BC. Cimon became a celebrated military hero and was elected to the rank of strategos after fighting in the Battle of Salamis.

One of Cimon's greatest exploits was his destruction of a Persian fleet and army at the Battle of the Eurymedon river in 466 BC. In 462 BC, he led an expedition to support the Spartans during the helot uprisings.

This expedition ended in humiliation for Cimon, because of Spartas refuse to accept the support of Athens.

As a result, he was dismissed and ostracized from Athens in 461 BC; however, he was recalled from his exile before the end of his ten-year ostracism to broker a five-year peace treaty in 451 BC between Sparta and Athens. For this participation in pro-Spartan policy, he has often been called a laconist. Cimon also led the Athenian aristocratic party against Pericles and opposed the democratic revolution of Ephialtes seeking to retain aristocratic party control over Athenian institutions.

The last ostracism in Athens

The last ostracised Athenian was Hyperbolus son of Antiphanes. It was sometime in the years 417-415 BC.

According to Plutarch, a fierce struggle unfolded in Athens between two groups, one of which (led by a rich man and a prominent commander Nicias) advocated a peaceful policy, and the other (led by the representative of the tribal affect Alcibiades) - for continued expansion in the west (in particular, in Sicily). The National Assembly decided to perform ostracophoria so that the Athenian demos would choose one of these two. Perhaps it was Hyperbolus who initiated the procedure: he belonged to the "war party" and won in the event of the expulsion of both Alcibiades (his rival) and Nicias (a representative of a hostile group). However, events went according to a scenario unexpected for Hyperbolus. Before the ostracophoria, Alcibiades contacted Nicias; politicians, unsure of the result of the ostracism procedure, agreed to facilitate the expulsion of a third person - Hyperbolus. What exactly they did is unknown. Alcibiades and Nicias could offer their supporters to vote for the expulsion of Hyperbolus, publicly criticize the general decision of the opponent, thus pushing the demos to a certain decision, or simply use the absence of disagreements between them, thus forcing citizens to look for some other other.

As a result, it was Hyperbolus that became a victim of ostracism. Neither he himself expected such an outcome (Hyperbolus felt safe, since he did not belong to the aristocracy), nor the citizens who cast their votes. According to Plutarch, what happened at first made the Athenians laugh, and then outraged: they were sure that ostracism should only be applied to noble and worthy people, and Hyperbolus had a reputation as a "worthless" man, a crook and a sycophant. “It was believed,” the historian writes, “that for Thucydides, Aristides and those like them, ostracism was a punishment, for Hyperbolus it was honor and an extra reason to boast.”

Plutarch argues that, under the influence of these events, the Athenian people abolished ostracism forever. This procedure was never really used again. According to a number of scientists, this is due precisely to the peculiarities of the last ostracophoria and its results: among the Athenians, the opinion could prevail that this procedure ceased to fulfill the functions assigned to it (in particular, the contradiction between the two main "parties" was not removed), the ostracism turned out to be unreliable a method of political struggle that could strike at its initiator, and therefore politicians were afraid to use it. Finally, the procedure could indeed be discredited due to the fact that an unworthy person became its victim. According to alternative hypotheses, the rejection of ostracism could be associated not with the expulsion of Hyperbole, but with a change in the general situation in Athens, with a deterioration in demography, with the absence of bipolar confrontation between political groups. There are also opinions about the combination of a general and personal reasons.

In the period between the last ostracophoria and the transition of Athens under the rule of Macedonia, a specific type of ostracism continued to exist - ekphyllophoria, which provided for the vote not of all citizens, but only of the members of the Council of Five Hundred (Boule). Unlike classical ostracism, olive leaves were used as bulletins instead of shards. The victim of ecphyllophoria was not to be expelled from the city, but from the Council of Five Hundred. The voting of judges for the exclusion of illegally entered persons from the lists of Athenian citizens was also called ecphyllophoria. In the internal political struggle during this period, they began to actively use the "accusation of against the law", "accusation of adopting an inappropriate law", etc. These procedures were trials that although they appeared before the last ostracophoria, they took over a number of functions of ostracism.

The graphē paranómōn (γραφὴ παρανόμων), was a form of legal action believed to have been introduced at Athens under the democracy somewhere around the year 415 BC; it has been seen as a replacement for ostracism which fell into disuse around the same time, although this view is not held by some reserchers

Any decision of the people (ψήφισμα), as well as any law, both before and after its adoption, could be challenged by means of such a complaint, on the grounds that the proposal does not agree with the existing law, or is harmful to the state, or contains a formal error. The application for filing such a complaint must have been accompanied by an oath (ύπωμοσία) that the prosecutor really has the intention to file it; at the same time, sometimes the appointment of a time limit for the trial was also asked. The immediate consequence of such a statement was that the debate was closed, or, if the decision had already taken place, then the law was invalidated until the court's verdict. The iniciator of the law before the expiration of a year after its adoption was subject to personal responsibility for the law he proposed. The punishment to which the accused was subjected, if convicted, depended on the will of the judges; he could be sentenced to fines (usually) ranging from insignificant to huge, and in rare cases even to death.

Very many of the known prosecutions concern not substantive legislation but honorary decrees, seemingly of little importance from a modern viewpoint. These did however allow discussion of a wide range of questions and issues.

Later, in the hands of demagogues, graphē paranómōn also turned into a means of preventing the promulgation of the necessary laws, or at least slowing down their approval.

*****

Peisistratus had achieved a reconciliation with Megacles, who not only helped to restore his power in Athens but gave to Peisistratus his daughter Coesyra (Cleisthenes' sister). Having become tyrant of Athens again, Pisistratus fulfills his promise to Megacles and marries his daughter.

However, as he didn't want to get his new wife pregnant and he has sex with her "οὐ κατὰ νόμον" (“not in accordance with custom”). Intercourse with a spouse "not according to custom" was hardly approved by society; the wife could be considered disgraced and her father dishonored.

Coesyra at first kept this a secret, but then, perhaps under questioning, perhaps not, she told her mother. Her mother told Megacles. He was exceedingly angry about the dishonor Peisistratus had done to him. Megacles made up his quarrel with his political adversaries. When Peisistratus learned of the moves being made against him, he immediately fled the city.

The divorce from her provoked the second overthrow of Peisistratus.

This time Peisistratus assembled an army and invaded Attica. Megacles and his clan were once more banished; and, though he and Cleisthenes continued to plot against Peisistratus, they did not succeed during the tyrant’s lifetime.

The origin of how one of the oldest cities in the world, Athens, attained its current name is a mithical story. Although few people are aware, the city actually had several names throughout its 3,400 years of recorded history.

Aktaios (Actaeus)

According to Ferekidis, he was the father of Telamon and a friend of Peleus.

According to Pausanias, he was the first king of Attica. His daughter Agravlos married Kekropas, who was placed on the throne of Attica by Kranaos.

The foundation of Athens is lost in the old myths and legends, as it is generally believed to have existed even in the Mycenaean era.

Kekropas (Cecrops)

Its second name, Kekropia, was derived from King Kekropas.

According to legend, the lower part of his body was the same as that of the dragon. During his reign, the goddess Athena and Poseidon vied to protect the city and offered gifts.

Athens (Athína)

There is a rich and mythical history all around the city, and the way in which Athens was named is no exception to having a magical story unfold.

The story starts with a duel between the ancient gods of Olympus to determine who would give it their name and become its patron. It is said the god of the sea, Poseidon and the goddess of wisdom, Athena made it to the final round where Zeus intervened in order to avoid a violent fallout. Zeus declared that each of the gods had to present a gift to the city’s king, Cecrops, who was a half-man half-snake creature, and whichever gift was accepted by the citizens would determine the new name of the city.

Legend says that all of the citizens went high up on a hilltop to witness the offerings of Athena and Poseidon. First up was Poseidon who struck the rock of the Acropolis, opening a spring of water, offering the new city success in war and at sea. However, the people tasted the water and were not enchanted as it tasted salty, as the seas that the god reigned over.

When it was Athena’s turn, she stepped forward and planted a seed into the ground which immediately sprouted up into a beautiful olive tree. This was the goddess’ gesture of giving fruits of peace and wisdom, as well as the tree providing them with oil, food and wood for burning and tools. According to the fable, the men supported Poseidon while the women, who out-voted the men, were in favor of Athena.

As the citizens named their city Athens, the owl, which signifies wisdom and was connected with Athena, became the choice pet animal of the Athenians. When money was invented, the goddess Athena was depicted on one side of the drachma coin while the owl was on the other. The citizens of Athens built temples, statues and held festivals dedicated to their patroness, Athena.

It is very noteworthy that even the current name - Athens, according to legend, the City received as a result of VOTING, which once again indicates that Athens is deservedly considered as the cradle of democracy.

In fact, the references in the legends about the adoption of collective decisions on important issues may suggest that elements of democracy in one form or another were present long before the Classical, and even Archaic period of Greek history.